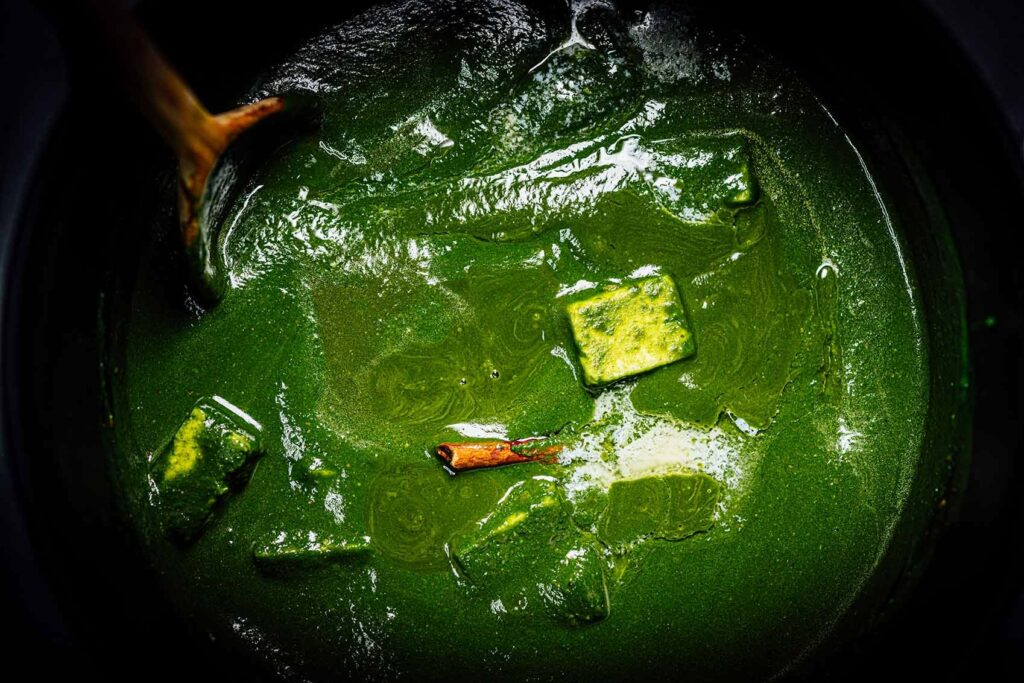

Palak Paneer Before we begin, let’s get to know paneer a little better. What Is Paneer? One of the issues that often come up in food writing, especially for some of us writers who work with non-European ingredients, is that we need to describe them using a more familiar counterpart even if there isn’t one. Take paneer, for example; it’s often called “Indian cottage cheese” or “Indian cheese”. While paneer is a form of cheese, that description is misleading. People who make paneer for the first time and aren’t familiar with it expect it to be salty. Almost all European cheeses are salted, but paneer is not. Paneer isn’t the only example; kulfi, a frozen Indian dessert, is described as an Indian ice cream. This description conjures up images of soft scoops of ice cream, and kulfi most certainly doesn’t qualify. Kulfi contains ice crystals and is firm enough that it can be cut with a knife. Kulfi’s texture lies between a milky ice cream and a sorbet, but is firm. While I’ve used these descriptions when I write recipes to introduce ingredients and provide some kind of comparison, I often wonder if I’m setting the stage up for misconceptions. To understand why paneer is made without salt, let’s first see how paneer is prepared. Paneer is obtained by curdling boiling milk using an acid like lemon or lime juice, the whey is drained and discarded, and the curdled milk solids are collected. The milk solids are then rinsed well and then pressed to form a cake which gives the paneer its characteristic block-like structure. Salt is never added at any point, whether you make it at home or buy it from a grocery store or an Indian market. Paneer is a firm product and is not a spreadable cheese. It also doesn’t melt when heated, making it amenable to frying and other heat-based applications as it holds its structure. For this reason, paneer is added to dishes like today’s palak paneer and grilled on skewers to make kebabs. Homemade Paneer Is Often Too Soft Some of you who’ve made paneer at home might wonder why the paneer you’ve made isn’t as firm as the one you’ve bought from stores. There is a reason for this, and it lies in the chemistry of milk. In India, buffalo’s milk is more common than cow’s milk and is often the source for paneer making (Cow’s milk is more prevalent in the West). Homemade paneer made from cow’s milk usually ends up like ricotta; it’s difficult to press it into a block and cut it into cubes that hold its shape. The calcium content of milk from cows and buffalos (cow’s milk has significantly lower calcium than buffalo) is very different, affecting the degree of firmness. When I was working on The Flavor Equation cookbook (learning how to make paneer using the recipe from the book), I tested cow’s milk with different types of cooking acids. After multiple rounds of paneer making, I found that adding calcium chloride (an ingredient used in cheese making) along with lemon juice to cow’s milk helped produce firm paneer just like the one sold in stores, it was also easier to press and shape, and then cut the cubes of paneer held on to their shape. Adding calcium chloride increased the calcium content of cow’s milk and helped with the curdling of the milk (calcium chloride is an acidic salt and, when dissolved in water, lowers the pH and changes the electrical charges on the amino acids in the milk proteins). You can also read more about it at Serious Eats. Paneer takes on the flavors of whatever it is exposed to (like tofu) and is high in protein, making it extremely popular in Indian cooking. Palak Paneer Palak paneer is sometimes called saag paneer. Saag is the Hindi word for green leaves, and you can make this dish with mustard greens (the most common choice, especially in the Indian state of Punjab where mustard is grown) or spinach (the Hindi word for spinach is palak), but you can use any type of green leaves. If you think of a Venn diagram, saag paneer is the big circle, and palak paneer is the smaller circle inside it. Some of the saag and palak paneer recipes will call for the addition of kasoori methi, aka sun-dried fenugreek leaves. You can buy this online or find it in an Indian grocery store. A little bit of this goes a long way; some people discover the flavor of fenugreek a bit potent, so use it accordingly or skip it. To Fry Or Not To Fry As a child, I would only eat paneer fried if it wasn’t; it felt like my world collapsed (I was a dramatic child, and I think as an adult, I’ve mellowed somewhat, but my family and friends might disagree). For no particular reason, I now prefer paneer in stews unfried, the texture feels so much more tender and delicate, and I love that. If you want to fry the paneer, do so by all means. A couple of pointers before you make this dish. First of all, I am not convinced that 8 oz/230 g of paneer is enough to feed four people even as a side. Luckily because this recipe makes plenty of gravy, I’ve provided the option to double the paneer (so it can actually feed 4 people as a side or main), but I will leave this up to you. Some people prefer less paneer and more gravy. READ THE COOK’S NOTES. Where To Buy Paneer – Indian Grocery Stores, Whole Foods, and many other grocery stores now sell paneer in the dairy aisle. You can buy a couple of blocks and freeze them. Thaw a block the night before you plan to use it. Now, let’s make this pot of palak paneer. 4.5 from 2 reviews 2 Tbsp water 1 medium onion, diced /150 g 1 Tbsp fresh ginger, peeled and chopped 4 garlic cloves, chopped 3 Tbsp/45 ml ghee, unsalted butter, or extra-virgin olive oil One 2 in/5 cm piece cinnamon stick 1 Tbsp ground coriander 1 ½ tsp garam masala homemade or store-bought 1 tsp whole cumin seeds ¼ to ½ tsp ground cayenne 1 tsp kasoori methi (optional) ¼ cup/60 g plain, unsweetened Greek yogurt Fine sea salt 8 oz or 1 lb/230 g or 455 g paneer, cut into 1 in/2.5 cm cubes (See The Cook’s Notes)

Comment * Name * Email * Website Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Δ